- Home

- Pharr, Wayne

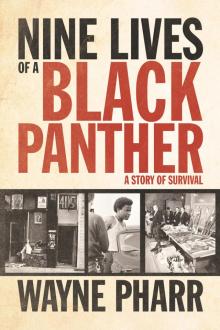

Nine Lives of a Black Panther Page 3

Nine Lives of a Black Panther Read online

Page 3

I learned from Uncle Edwin not just how to fight, but how to win. My aunt told me that one night some people tried to rob Uncle Edwin at his after-hours spot. He took a baseball bat and beat three of them up real bad. We talked about it one day, and Uncle Edwin told me that holding your fist up is just posturing; using the baseball bat was about winning. “A man ain’t no man if he don’t stand up for himself. You hear me, boy?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You don’t take no shit from nobody, and you don’t run from nobody neither.”

When I was fifteen, Uncle Edwin had a stroke and his speech became slightly garbled, but even then he still had that same personality. After the stroke, sometimes people couldn’t understand what he said. One time I heard Uncle Edwin talking to one of his friends, who was having a hard time comprehending him. “If-i-hit-you-in-the-hey-wid-this-hamma-you-will-know-what-i-mean!” he slurred in frustration.

After that, I really tried to listen closely to what Uncle Edwin said, so he wouldn’t hit me in the head with a hammer. Uncle Edwin was something else. I wanted to be just like him. I really valued the time I was able to spend with him, and he took special pride in knowing that he was partly responsible for my life.

About 1952, Nanny moved from Vallejo to Los Angeles and purchased a home on San Pedro Boulevard. Her brother, Fred Prescott, had been there for a decade, so Nanny already had family to welcome her to the city. My mother followed Nanny to Los Angeles after she and my dad separated. I never knew the reason for the separation; adults rarely shared those personal details with kids back then.

Always looking for a way to leave domestic work behind, my mother thought moving to Los Angeles would provide new opportunities, and her aim was to get a job working with the post office once we settled in. I knew I would miss my relatives in the north, but from the stories my mom shared, I was eager to meet my family in the City of Angels.

My mom started out as a domestic in Los Angeles, but around 1955 the postal service finally hired her. I was about five years old and had just started school. When my mom was at work, I would go visit other family members. Eventually, my mom was assigned to work the swing shift, and so she went to work at night. Of course, that’s when I would sneak out of the house and go hang out with my relatives and friends in the neighborhood.

After my mom and dad separated, I did not see Dad much. He was often deployed, but he would send me gifts every now and then, like portable radios and the latest electronic equipment. When I was around ten, Mom took me up to Oakland to visit Dad, who at that time was living in a place called the California Hotel. It was a four-story brown brick building, and his space was quite small, with just a bed, a living area, and a kitchenette in one room. Because he was a navy seaman, he didn’t bother with owning a home or even renting an apartment.

We had a pleasant conversation that day, but nothing earth-shattering. He called me Champ.

“How you doing in school, Champ?” He was looking at me with a smile.

“I’m doing well,” I answered politely.

“Are you helping to take care of your mom?”

“Yes, sir, I am doing my best.”

I was quiet and did not have much to say, but I checked out the environment, curious about how my dad was living. We talked a little bit more and then my mom and I left. That was it. Even though my mom and dad talked periodically, they didn’t raise me together.

I loved living in Los Angeles. Holidays and regular weekends meant nothing but fun and family get-togethers. I had a large, close-knit family. Nanny’s brother Uncle Fred had fifteen children, and they all had children, so I had a whole gang of cousins I could hang out with. My father’s brother, Uncle Bill, lived in Los Angeles too. Uncle Bill’s daughter, Doretha, worked in the undertaking business, which seemed like a gruesome line of work. But everywhere I looked in my family, I was able to gain insight into the importance of earning a living and eventually owning a business so that I could work for myself.

One day after school, I ran into the house excitedly. “Mama, I know what I wanna do with my future!” I could hardly wait to tell her my news.

“What you want to do, baby?” I could tell my mother was interested.

Kindergarten class photo of me at the age of five. WAYNE PHARR COLLECTION

“I want to establish my own business, like Doretha and Uncle Edwin. I want to start a car washing business.”

I was excited and proud about my decision, but my mother’s interest evaporated as quickly as it had appeared. “Wayne, no child of mine is going to wash cars! You will do better than that.”

“But why not?”

“I’m not working as hard as I do so that my child can go clean somebody else’s car! I don’t clean other people’s houses no more, and my child is not going to clean other people’s cars … other people’s anything!”

I was speechless.

Quietly, she mumbled, “I can even accept you running a gambling house. At least you would make a lot of money.”

I barely heard that last declaration, but I wasn’t surprised about my mother’s under-her-breath statement about gambling, and I knew she was somewhat serious. My mother understood and appreciated hustling. The postwar years had brought opportunities for employment to low-skilled workers in Los Angeles, so everybody in my family was doing something—either working or hustling.

After a while my mother remarried. I didn’t really pay attention to their courtship, but I thought that her new husband, Mr. Oscar Morgan, was a fine gentleman. Mr. Morgan was tall and had kind eyes. There was an important air about him, and he was always well dressed in a suit or shirt and slacks. He was a college-educated man, a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, and he taught junior high school math. Soon after they married, Mr. Morgan and my mother bought a house on Eighty-Third Street and Avalon and I started going to South Park Elementary School. I had happy times with Mr. Morgan as my stepfather. He was very different from Uncle Edwin, so I learned a new way of viewing life from him. He pointed things out to me and taught me about being a gentleman. We watched TV together, mostly movies and animal and nature shows. We also listened to jazz together, and one day in particular, as we were sitting on the living room couch, I learned from him how nuanced the world was and all the many things I still didn’t know about life.

Mr. Morgan turned the television’s volume up slightly, calling my attention to it. He moved toward the edge of his seat and was leaning forward confidently, pointing his large but well-groomed hands toward the black-and-white images on the TV screen. He turned to me. “That’s Lester Young right there; he’s called the Prez, short for the President.”

I nodded earnestly.

“Listen to how he plays his saxophone; do you hear the difference from how Dexter Gordon sounds when he plays?”

“No, not really,” I admitted.

“Well, then you got to listen more closely,” he replied patiently.

I also learned how to maintain my cool from Mr. Morgan, and the importance of thinking before you speak. Mr. Morgan was quite a contrast to Uncle Edwin in this way too. Uncle Edwin was flamboyant and quick-tempered. I never saw Mr. Morgan flare up. But like Uncle Edwin, he was always teaching. He talked about the importance of knowledge, dignity, and serving our community. Standing in front of the mirror putting on his tie in the morning, Mr. Morgan took the opportunity to teach me things. “Knowledge is very important to a man, Wayne. Always remember that.”

“Yes, sir,” I nodded.

Then I went into my room and looked in the mirror to make sure I looked my best, just like Mr. Morgan. Between Uncle Edwin and Mr. Morgan, I was learning a lot about becoming a man—even though they lived in very different worlds and had very different styles.

Mr. Morgan and my mom were only married three or four years. I had no idea there was trouble in the marriage, even though my mother expressed a little displeasure sometimes. But Mr. Morgan, who was always calm and collected, never let on in his conversations with me. Then

one day when I was seven, my grandmother on my mother’s side, Lillian Brusard, came to Los Angeles to take me to Texas to stay with her. I realized later that I went because my mother and Mr. Morgan needed time to sort things out.

Celebrating Christmas with my stepfather, Mr. Morgan, around in 1956. These were happy times. WAYNE PHARR COLLECTION

My grandmother, called Honey by her friends, was short and matronly but very attractive, with a beautiful brown complexion the shade of toasted honey. She had left Louisiana during the great migration of African Americans from the South to the North, the West, and the urban centers of the United States. But instead of going to California like so many of my relatives, she moved to Port Arthur, Texas. I ended up spending a year with here there, getting to know the ways of the South.

I looked up to Grandmother Honey. I thought she was strong—she wasn’t going to let anyone push her around. She was very social, always playing cards with her friends—they played a game called cooncan, similar to gin rummy. She also loved to cook, and I was always the first kid to sit down in front of the red-and-white-checked tablecloth in the kitchen for a plate of her mouthwatering fried chicken, which was served with a tall glass of iced tea.

But my admiration of her strength was ironic, considering that it was my experience with her on our train trip from California that showed me the powerlessness and weak state of black people.

“See this here?” she had asked me, flashing me her pocketknife as we sat on the train pulling out of California.

“Yeah?” I said. My eyes were as wide as saucers. The knife was small and slender, with a smooth yellow handle.

“Anybody mess with us, I’m gon’ cut their throat!” she winked at me fiercely.

I thought my grandmother was the toughest woman in the world.

It wasn’t my first time on a train, but this particular train trip was one I will never forget. It took us two days to get to Port Arthur. My grandmother and my mother had cooked up a mess of fried chicken and biscuits the night before we left, wrapping them in aluminum foil and putting them in a large brown paper bag. This would have to last us for the duration of our trip, since we never knew which restaurants would serve black people.

As a kid, train rides were something of an adventure. The scenery out the windows was beautiful, and the compartments piqued my interest. I was so excited and full of energy that I spent a large part of my time running up and down the aisle looking through as many windows as I could.

And then the train conductor appeared. Looking up at this white man, I thought he seemed to be a giant, reaching almost to the ceiling of the train, a menacing sight. He wore a black hat and was dressed in all black except for a small gold bar on his uniform. Irritated, his voice boomed. “You can’t rip and run all up and down this aisle, boy,” he said to me with contempt.

I stared up at the Giant, not saying anything, then ran back to my seat and grandmother. The Giant followed, steadying himself with his hand on the seatback.

“Ma’am, you need to keep an eye on this boy; can’t have him running all over like this,” he said to Honey.

“I will,” she said to the Giant, placing her arm around me.

The Giant disappeared down the aisle, and my grandma soon nodded off to sleep. I slipped out of my seat and continued ripping and running, climbing onto seats, and looking through the windows. I headed for the end of the car, racing down to the door and planning to race back to the other end when the Giant made his move from seemingly out of nowhere. He had been hiding just behind the door leading to the next car. He waited until I ran up close and then opened the door fast and hard, boom!, busting me over my eye. I howled, equally from the shock as from the pain, and ran to my grandma, my protector, with the conductor quickly following behind.

There was a cut over my eye and it was bleeding. I just knew that my grandma was going to pull that pocketknife she showed me earlier and slay that Giant. My crying woke her up, but before I could even tell my version of what happened, the Giant boomed.

“I told you before to keep an eye on him; I’m not going to tell you again,” he growled, looking down his nose at her.

“I’m sorry, sir, really sorry. I’ll be sure and keep him close from now on,” my grandma apologized. “You sit your little self down right here and don’t you move anymore, you hear me?” My grandmother scolded me as she took some tissue and wiped over my eye.

I watched and listened in seven-year-old horror as my grandmother humbled herself before the Giant. I was crushed. The woman I thought was the toughest in the world, the woman who wouldn’t hesitate to use her pocketknife to cut someone who messed with us, had bowed down to this mean white man. Yet I was the one who had been busted in the eye and was bleeding! We rode the rest of the way in virtual silence, speaking only when necessary. I guess the truth is my grandmother and I weren’t sure what to say to each other. I was glad when we finally reached Port Arthur.

It wasn’t long before I began to understand segregation. I noticed that there were black water fountains and black bathrooms and white water fountains and, of course, white bathrooms. The schools were segregated too, as were the parks, beaches, and anywhere else you might want to go. I was confused about the lack of power that black people had, but I didn’t ask Honey why. I sensed that she was embarrassed by it, so I played stupid, as if I didn’t see it.

One day, I went to the Lincoln Theatre in downtown Port Arthur, the movie theater designated for blacks, with my new friends Donald and Carl. We were watching a cowboy Civil War movie, and at one point I was cheering and hollering for this one group of guys in the film to win.

Suddenly, I felt an elbow in my side. “Nigger, are you crazy?” It was Carl. “Those are the Confederates! They were the ones fighting to keep our people in slavery!”

I didn’t know that information at that age, but Carl did. Carl would later educate me on other important issues of race, such as what castration meant and how whites would do it to you if you messed with their women or if you were a bad nigger. “They’ll hang you up with some rope ’round a tree, and then they’ll take a knife and they’ll cut your thing off!” he told me breathlessly, placing his hand over his crotch.

I sucked in my breath, cringing. I recalled the graphic images of Emmett Till.

I witnessed another important event while I was in the South, which demonstrated to me the hatred some whites felt toward black people. Two years after my five-year-old eyes had been opened by the killing of Emmett, I watched white folks on TV engaged in angry mob violence, trying to stop black kids from attending Central High in Little Rock, Arkansas. One of the images was of a little black girl, walking by herself, trying to get through the crowd. They shouted and spit at her, calling her nigger and other horrible names. I could see the white people’s hate right there on the TV screen. It was a lot of hate. I began to understand why my grandmother didn’t try to stab the white man on our train trip. She probably thought a white mob might get us too, I reasoned.

Food was an interesting issue in the South. We would rarely eat outside the house. It may have been a good way to save money, but it also was a way to avoid facing segregated restaurants. Honey raised chickens and turkeys and made sure that we ate what we raised or grew.

One day, I was playing in the chicken coop and a rooster bit me. “Ouch! Ouch! Grandmother Honey!” I wailed.

“What’s wrong?” she called out from the house.

“The rooster bit me!”

My grandmother flew into the yard—I don’t remember ever seeing her move that fast. She swooped down on that rooster like nobody’s business. “Get ’way from him, you old no good …” Grandmother Honey grabbed that rooster, held his body with the wings back in one hand, and with the other hand she grabbed his head and twisted it all the way around. “Run, go get me a bag I can put these feathers in,” she commanded.

I ran as fast as my little feet could carry me. Over my shoulder, I could hear her still scolding the dead bird. I was horrifi

ed.

“We havin’ you for dinner tonight!”

In spite of the good food at Honey’s, I wished I could buy food at the cafeteria at school in town. I wanted to be like other kids, especially at holiday time. But I was not allowed. “Grandmother,” I pleaded, “can I go to the cafeteria to eat Thanksgiving lunch at the school?”

“No,” she said firmly. “I don’t have enough money to give that school any of my hard-earned savings. What’sa matter with my food, anyway?”

My grandmother made my Thanksgiving lunch, a turkey sandwich and a slice of sweet potato pie, which I took to school. My teacher, who was a kind woman, bought me lunch, which meant I had two lunches that day. The only time I was allowed to eat outside the house was maybe on Fridays, when I could go get a hot dog, and that was it.

In spite of the lessons of racism, my visit to Port Arthur was a great experience. Honey would sometimes take us to Bunkie, Louisiana, to see her other brother, Sugar. He had nine children, and I thoroughly enjoyed being with them. Another one of my great uncles, Willie, lived in Port Arthur with his wife and seven children. Donald, one of Willie’s sons, was my age, so we became running buddies. We would go off into the woods and shipyards. We would also play in Granny’s backyard, which was pretty much the Gulf of Mexico. My grandmother made sure I learned to swim because she knew she could not keep an active and rambunctious kid like me from the water. “I know tellin’ you not to go to the shipyard won’t do any good, so you gon’ learn how to swim,” she sighed. She took me to the Y for lessons.

In 1957, Hurricane Audrey hit Texas and Louisiana. Port Arthur sits on the east side of Texas, near the Gulf of Mexico, so we were hit pretty hard. Power lines and trees went down, and at least nine people died in our area. I remember because my grandmother made me go to school on the day it hit. There was no discussion about it; a hurricane warning was no excuse for a family that believed strongly in education and upward mobility.

Nine Lives of a Black Panther

Nine Lives of a Black Panther