- Home

- Pharr, Wayne

Nine Lives of a Black Panther Page 9

Nine Lives of a Black Panther Read online

Page 9

After some back-and-forth, eventually her husband agreed. He grabbed a shirt and stepped outside with us, slamming the door behind him as Anne tried to position herself to watch what was going down.

“What’s your name, brother?” Craig asked.

“Jerome,” the man replied, and then immediately began trying to justify his actions.

“Look, Jerome, we’re men too,” Craig began. “We understand how things can easily get out of hand, but hitting on sisters just ain’t cool, no way we slice it. These are the queens of our community. They bear the children for the nation, so we need to find another way to solve our conflicts.”

With that, Jerome had no comeback. He scowled in thought, not really knowing what to say, but I could tell he was considering the wisdom of Craig’s words.

We went on talking, trying to reason with him in a nonthreatening way. We pointed out that, besides the importance of taking care of our women, Jerome wouldn’t want to run the risk of going to jail. He was somewhat agreeable, finally calming down. It took us about half an hour, but by the end of our little chat, he was smiling and happy, assuring us he would go back inside and take care of his queen.

These kinds of interventions were not uncommon for us, and that first one with Jerome was a good experience for me. It was incidents like this that taught me how to talk to people respectfully and sincerely listen to what they had to say.

Many times these encounters left such a positive impression on the neighborhood that we became more effective in recruiting and mobilizing. In fact, the Watts office became one of the most productive offices in Los Angeles. Al Armour was so impressed with my work that he soon began letting me run the office. To this day, I am thankful to Al for that opportunity, because I carried those experiences with me throughout the rest of my life. Everything I know about managing an office I learned while I was in the Black Panther Party.

Most party members sold the Black Panther newspaper to raise money. For me, selling the newspaper was one of the best parts of my work because it required me to leave the office and go into the community and interact with people. I also sold papers at Harbor College, which helped me to maintain my connection with the students. Other times, I would drop them off with a BSU member and come back later to pick up the proceeds.

Russell Washington was in charge of distributing the papers. We connected immediately the first time he came by the office to pick up the leftover papers and collect the money from our sales. I was in the office with my head deep in some paperwork when Russell walked in. “Is this the place where they’re selling them revolutionary papers?” he queried boisterously. “I heard it was.”

“Sho ’nuff,” I replied. “You ain’t never lied. How many bundles you want to buy, good brother? That’ll be the best thing you ever did for the community,” I finished with a hearty laugh.

Russell broke out in a wide grin, then strode over and gave me a vigorous black power handshake: two strong moves where we first clasped our hands together with thumbs on top, then pulled each other’s fingers as we drew our hands apart. From that day on, the two of us just found it easy to flow with one another. We just clicked like that.

Sometimes I’d even roll with Russell on his collection runs. Afterward, we liked to sit down over a drink and share political analyses, including our ideas about how the Party could continue to move forward. Russell liked to drink what we called Bitter Dog, sometimes referred to as Panther Piss, a combination of white port wine and lemon juice. It was popular with a lot of the brothers. It was an old-school ghetto drink that would get us high and didn’t require us to dig too deep into our pockets to get there. Personally, I was more into beer, particularly Country Club Malt Liquor, but in its absence I wouldn’t turn down some Piss. Before we took a swig, we’d always pour a little for the brothers who weren’t there—dead or locked up. I admired Russell. He knew the streets of Los Angeles very well, including all the shortcuts for getting around town.

For me, the work for the Party didn’t seem like work; it was a commitment, my raison d’être. At times, though, I had a lot of fun with my comrades just blowing off steam. For instance, Nathaniel, Lux, and I would sometimes hang out at Al’s graveyard-shift security job in the twenty-four-hour funeral home located on Forty-Eighth and Avalon. The place stayed open ’round the clock to serve people who wanted to visit their deceased loved ones at any time of the day or night. Nathaniel’s fool behind would actually play with the corpses, which scared the daylights out of me. The first time I saw him do it, I thought it was just plain creepy. I said to him, “Man, what is wrong with your crazy ass, playing with dead people?”

“Yeah, man,” Lux chimed in, “somebody’s relative is gonna come in here one night and find your ass playing with their mother, then whup your fool behind.”

“Aw, man, chill out,” Nathaniel said as he tickled one of the bodies. “We just having a little fun. Besides, the dead, they don’t mind at all.” With that, he busted out in laughter, thinking he was witty.

Staring at us, shaking his head with an I-don’t-believe-I’m-watching-this grimace, would be Al, nursing his Piss, looking from one of us to the next, as if he were sitting in a comedy theater.

Even though I loved those nights we hung out at Al’s gig, I was a little nervous about being around dead people. I could swear I heard noises in the coffins sometimes, even when I knew it wasn’t Nathaniel joking around.

In addition to the work we did at our offices, all comrades were required to go to the Panther headquarters once a week for office meetings. The headquarters was located on Central Avenue, one of the most popular and famous streets in Los Angeles. During the 1940s and ’50s, jazz clubs populated the area, along with black businesses such as insurance companies, hotels, and the offices of African American physicians. It was also the place where jazz artists from all over the country would play, including greats like Louis Armstrong, Charlie Mingus, and Lionel Hampton.

The Black Panther Party headquarters at 4115 South Central was the hub of all Panther activity around the city. The office was a two-story brick building that at one time had served as a store. On the side and up a flight of stairs was 4115½, where we had more offices. In order to enter that part of headquarters, we had to go outside and walk up the stairs along the outside of the building. Altogether headquarters had plenty of space, about two thousand square feet. In the downstairs area were the general office, the gun room, and a large room with a back door. Located upstairs were the meeting rooms and areas for communications and printing. In addition to Central Headquarters, Party leaders operated out of apartment buildings and other houses to throw off police.

James hipped me to the chain of command that governed the Party. “It’s rather simple to follow,” he explained. “There’s an order of leadership at the national level, and this same order is replicated in each of the Party’s local branches. There are ministers, as you already know, at the national level, and all local chapters have ministers as well. The ministers at the national level are organized into a Central Committee that governs the organization. All local ministers, of course, are subordinate to the Central Committee.”

Having already done extensive research on the Party before I joined, I knew a lot of what he told me. I didn’t want to offend him, though, so I nodded attentively to everything he said.

He continued, “For example, in the L.A. branch of the Southern California chapter, Bunchy Carter is the deputy minister of defense, which corresponds to Huey’s position as minister of defense on the Central Committee.”

“Who appoints those lower in command at each office?” I asked.

“It’s the minister of defense’s responsibility to give members their rank,” James explained. “So Huey gives rank on the national level, and consequently Bunchy gives out rank at our local level. Does that make sense? You see the parallel?”

“Yeah, I see it clearly. Bobby Seale is chairman of the Central Committee and Shermont Banks is deputy chairman here.

Eldridge Cleaver is the minister of information nationally, and John Huggins is the deputy minister of information locally.”

“Yep, you got it down cold,” James said with a look of approval. “Also remember,” he added, “that political awareness and dedication to the cause would get someone appointed section leader by Bunchy.”

I nodded my head, wondering if that was what James was aiming for.

I had already had a brief encounter with Deputy Minister John Huggins before I joined the party, the day I had gone with the brothers up to UCLA. To me, John didn’t really look like your average Panther. He wore the kind of clothes you would expect to see on a white hippie, thrift-store stuff, sort of mismatched clothes. He was a light-skinned dude with a big curly Afro. He had come to Los Angeles from Pennsylvania with his wife, Ericka, to join the Black Panther Party. That day at UCLA, he welcomed me to the meeting with the words, “Glad to have you, comrade.” I had smiled and clasped his hand. I could tell that Huggins was easygoing and had a friendly personality, and I immediately liked him.

Elaine Brown, a beautiful sister with deep, soulful eyes and a smile that could light up a room, was the secretary of the Southern California chapter. Elaine was always busy, and I could see that she was deeply committed to our work. Ronald Freeman and Long John Washington were field secretaries. Their job was to travel throughout the Southern California region to check on the offices and the work of all Panthers. Whenever they showed up, they were in charge.

There were also several captains operating out of Central Headquarters. I was already familiar with two of them before I joined the Party: Frank Diggs, who was nicknamed “Captain Franco,” and Roger Lewis, whom everyone called Blue. I knew Captain Roger “Blue” Lewis from the neighborhood, going back to when I was a kid, but I didn’t know him well. He was a clerk at a shoe store, and I used to run into him regularly. He was a dark-skinned brother who had a disarming smile and a real charismatic personality, real easygoing. I respected him.

I had met Franco in the neighborhood when he tried to recruit me into the Party. He wasn’t a big guy, about five foot nine with kind of a medium build, but what he lacked in size he made up for in intensity. Tyrone introduced us to each other. We were just leaving a party one night when Frank strolled on up.

“Captain Franco, what’s up? I want you to meet my homeboy Wayne,” Tyrone said, slapping me on the back. “He’s a Broadway Slauson and also a student out at Harbor College. But he’s not letting all that book knowledge blind him to the reality of our struggle for the people.”

I nodded at Franco coolly.

“Sounds good,” Franco said forcefully. “We always need brothers with their heads on straight. So have you joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense?” he pressed.

“Thinkin’ about it, brother,” I replied.

“And I do put emphasis on the self-defense part, Brother Wayne,” Franco finished, in an official sounding tone.

“I’m seriously checking it out,” I calmly replied.

“Well, don’t wait too long, because whitey ain’t waiting at all to put his foot down harder on the necks of our people. Study long, study wrong.”

I looked at Franco without saying a word, deciding to back off. I realized then that he had what seemed to me a crazed look about him, and I didn’t want to push any buttons. Who knew what might have resulted from that.

Right on cue, Tyrone said, “All right, Captain Franco, we gonna push on. We’ll catch you later.”

“All right then, brothers,” Franco answered. “But remember, the black man will never be free until he can look the white man in the eye and kill him. Especially them fuckin’ pigs, who think they can’t die or something.”

As we walked away, I stole a long look at Franco and made a note to myself to always be alert when he was around.

Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt was another captain who operated out of Central Headquarters. G, as we called him, was a commanding presence, and I could tell immediately that he had military training by his stance and demeanor. He was medium brown, short, and bowlegged, with an air of physicality about him, always in motion. Word was that he fought in Vietnam but returned to challenge racism because he had seen so much discrimination by his fellow US troops. Bunchy had given him the name Geronimo ji-Jaga, indicating that he saw Geronimo as part of a tribe of strong and feared African warriors.

G and I met after a political education class at Central Headquarters one day. The meeting had already broken up and most people were gone. I noticed him, Long John, and Blue competing against each other in a knife-throwing contest that stabbed several holes in the office door. I sat quietly, watching them, entertained by their competitiveness.

After the contest, G walked over to me and said, “Right on, brother. Thanks for joining the organization.” Apparently, someone told him that I was a new member.

“All right, man, power to the people,” I replied. I was pleased that he took the time to acknowledge me, because I knew he was a major player in the organization.

Later, back at Watts, I asked James about him. He explained, “Blue, G, and Frank are all captains under Bunchy.”

After listening to other comrades rap about the three captains, I got the sense that they also did some of Bunchy’s dirty work—or rather, if Bunchy had a problem and didn’t want to handle it himself, he could rely on one of them to handle it for him.

After two months in the Party, I had met so many new people I thought my head might spin off trying to remember them all, and my life had changed drastically. What was I thinking? I wondered when I thought about all I was trying to do. I was serving as the elected president of the BSU at Harbor and working heavily with the Black Student Alliance on other college campuses and training students to become activists. And then I was a Panther.

In my student life, I was closest to Jerry Moore. I thought he was one of the most politically astute of the student activists. He was a few years older than me and a former Baby Flip from Slauson Village. I knew Jerry and his sister from Edison Junior High, and now he was a student at Pepperdine University, studying law. Jerry and the BSA supported the Black Panther Party and often supported our members who were underground. Aboveground, Jerry had a job at the Ascot library on Broadway and Seventy-Eighth, and he allowed the Black Panther Party to use its facilities to hold meetings.

Jerry was affiliated with the United Front and various organizations designed to uplift people suffering from race and class oppression. It was through Jerry that I developed a relationship with Diana, a Hispanic activist whose family owned a restaurant on Alvera Street. She introduced us to the Brown Berets and other Hispanic radicals. Meeting activists of other races and nationalities was good for me, because it just reinforced the idea that black people weren’t the only ones suffering and that working with other groups was essential.

Baba and Yusuf were BSA members who went to Southwest College; they were also strong figures in our activist crew. Both had done time before, but instead of going back to street life they enrolled in school. Baba, Yusuf, and others, including Wendell and Jackie, used to stop at Jerry’s house for political conversations. We were always debating, and we had great discussions. I really looked forward to those discussions because they were so stimulating. In fact, I began to hang out at Jerry’s place so much that eventually I moved in.

As a member of the Black Panther Party and a student activist, I would speak at campuses about the Party. It got to be something I was pretty good at, standing and rapping as a crowd would begin to gather.

“Listen up … I need to rap to y’all for a minute. Need to put something on your mind. Something that can help you find clarity about all the craziness you see around you. Things like why black and brown people are always down and whitey and his pigs are on the top. What’s that all about, huh? Somebody tell me. What’s that all about? Well, the Black Panther Party can tell you what’s it’s about and what you can do to fight it.”

I would talk about the B

lack Panther Party’s Ten Point Platform, telling my audience that it made a lot of sense. I would explain the nature of racism in the United States and then discuss the need for black people to have the ability to determine our destiny.

“Some have accused the Party of being racist. The Party is not a racist organization; we believe in Black Nationalism and self-defense as laid down by Malcolm X, but we also believe in power to all people! The Black Panther Party works in solidarity with all people for the common good.”

In some of my speeches, I emphasized the injustice and racist nature of the war in Vietnam. “What does power really mean? It means the ability to say no to war, especially no with our precious lives: the lives of our brothers, uncles, friends, and neighbors. Why the hell should we travel to the other side of the world to kill and be killed? What’s in it for us? Not a damn thing. You know that. I know that. The Black Panther Party knows that. If somebody just rolled up in your living room, shooting up your house, destroying your hard-earned stuff, you would deal with them, wouldn’t you? You’d have to, or be offed. That’s exactly what the yellow peoples of Vietnam are doing. They are dealing with invaders, attackers, thieves, destroyers, and robbers, strangers who have come to take their stuff—their land, their wealth, their self-governance. We black people can’t be caught up in the middle of whitey’s craziness, especially when it means our well-being and our lives. Get the hell out of ’Nam, whitey. Power to the people.”

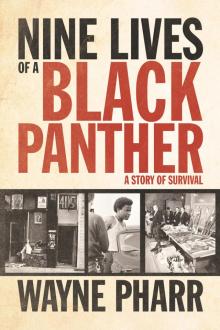

Recruiting for the Black Panther Party in 1969 during a May Day Rally at Will Rogers Park in Watts on 103rd Street and Central Avenue. Craig Williams, a Party member who worked with me out of the Watts Office, is also pictured. COURTESY OF ROZ PAYNE

Nanny and my mother were fully aware of my decision to join the Black Panther Party. When I joined, I didn’t make a grand announcement of it, because I wasn’t the type of person who would talk a lot about my personal thoughts, nor would I bring my outside issues into my family. But I think my disposition must have changed shortly after I joined and began to incorporate the Black Panther Party into my life. I know they noticed. I became more intolerant of mainstream stuff, like entertainment on TV. Shows that I might have stopped to take in or accepted as just killing time before, I now had total disdain for. This attitude left me out of some conversations with my family. I didn’t want to be antagonistic or anything, but who gave a damn about Jackie Gleason, Lawrence Welk, or any other tired-ass aspect of cracker culture? Surprisingly, this extended all the way to sports and athletes too. I wasn’t able to just jump in and jive about the latest matchups like I did in the past. My always-on analysis kept me keen on the exploitation involved.

Nine Lives of a Black Panther

Nine Lives of a Black Panther